Academia has no tolerance for disability, even as academia is disabling in and of itself

A guest post by Holly Genovese

Years ago, as a teenager, I stumbled on an interview with an academic who claimed he wanted to get his PhD so that he could add “to the sum of the world’s knowledge.”1 I was 14 years old, naive, and had no idea what was in store for me, not even for the rest of high school, college, or what might come after that. But his words resonated: I could contribute to “the sum of the world’s knowledge.” I still believe that I have something to contribute, even on my worst days. And because academia still privileges the able-bodied, “the healthy,” the upper middle class—other perspectives, including my own, are even more significant, even as they are buried.

But graduate school is hard.

It’s “supposed to be,” for no pedagogical reason I can understand. But it is meant to be hard. It’s rigorous—for me, it has meant years of coursework, working as a TA, reading 300 books for an oral exam, writing a prospectus, teaching my own class nine times, and, of course, now writing a dissertation. A document that is not a book but is, however, the length of a book.

PhD work is physically taxing—not in the same way that manual labor is, but in a manner that has an accumulative effect over time. Every year, my vision gets worse from eye strain, from reading, and from staring at the computer screen for long hours. Sitting in chairs is similarly terrible, causing back pain and neck strain. I once sprained my wrist from holding my Kindle. Graduate school slowly, slowly wears on your body.

To be clear, becoming disabled is not a bad thing. Last year, after performing in a Queer/Crip Fashion Show by Rebirth Garments, I wrote,

Because after all, that’s what the night was about. Imagining a different world into existence, one in which our queer/crip selves could exist fully and openly and loudly, decorating our mobility aids and matching our ear plugs to our outfits, dancing as stimming as jumping as walking as falling as sitting as being present. As operating on crip time, on queer time, on our time. Our disabilities, our queerness, our being, our breathing is beautiful and there, in that time/space/room, we could be ourselves as clearly as we wanted. Even in Texas, as our rights and the rights of trans people and drag queens and educators and students are stripped away, that room was our creation, was full of possibility, was full of what the world can be.

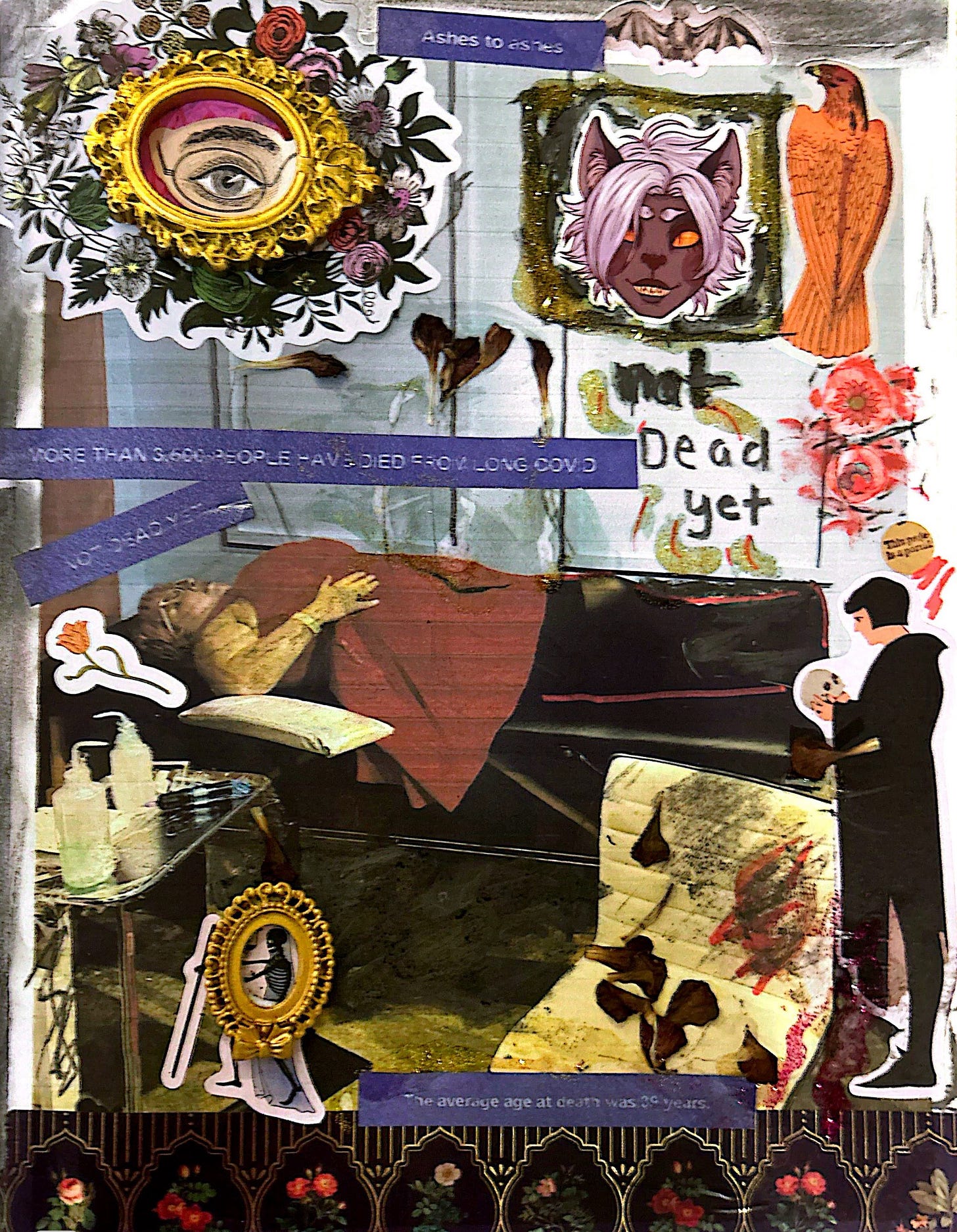

But the cruelty of academia is that “it” has no tolerance for disability, even as academia is disabling in and of itself.

Reflecting on my experiences in graduate programs

Graduate school is meant to be difficult and intellectually challenging, even for able-bodied cis white men. Every marginalized status multiples this challenge, some much more than others. I am a trans, non-binary queer, fat, mad, neurodivergent, disabled, chronically ill, and lower middle-class graduate student. Though I hold many privileges (I am, after all, white, a citizen, and never incarcerated), academia was not designed for me, much less the “public ivy” I managed to get into.

I have attended three different graduate programs. The first time, straight out of undergrad, I got into a fully funded MA program and attended (in history, a unicorn). The coursework there is still the most challenging academic experience I have had. Academics trying to prove themselves as smart as those at the ivy’s are almost always as smart but even more “rigorous.”

The second time I went to graduate school, I went back “home” to my undergraduate university for my Ph.D. It was a bad fit; it was not the place for me, but I loved my advisor and desperately wanted to live in Philadelphia. I had my funding taken away after a particularly horrible semester, a semester in which I experienced a mental health crisis and a crisis of faith in my career, my program, and my purpose. But I still wanted academia. I felt like it was, in many ways, meant for me.

My "bad year” (what I refer to as the year between leaving Temple and starting at UT, the only year I haven’t been in school since I was 4) made me feel even more confident that I wanted academia as I surreptitiously audited classes at Penn (steal that knowledge, as Moten and Harten have taught us),2 taught Black Literature at a senior center, and used my savings bonds to pay application fees. It felt like it was my last chance.

The third time I went to graduate school, I worked with “The Professor is In” on my application documents. I took an insanely expensive GRE course. I hired a developmental editor for my writing sample. It was, looking back, a little absurd. But it worked. I got into programs, this time in English and American Studies. I got into the “public ivy.” I ascended (for good or ill; I haven’t decided)

My Ph.D. program was hard from the start, of course. The coursework was not as hard as that in my MA program (thank god), and my fellow students were no more or less brilliant. But I read the books, wrote the papers, and attended conferences starting in my first year. I planned events, brought in speakers, and helped edit a journal. I read all 300 books (really, truly) and passed my orals.

Getting sick

But at some point, I started getting sick. In the words of young adult author John Green, “It happened slowly and then all at once.” I spent Fall 2019 in the ER at least twice a month, unsure as to why my heart was out of control. I was fainting during my periods, having constant tachycardia. I was diagnosed with Hashimotos a few YEARS later, but by then it seemed the least of my problems.

When COVID shut down the university in March of 2020, I was COVID-safe to the point of agorophobia. I knew, because of my mental health issues, my weakened immune system, and my heart that would just not slow down, that I was highly susceptible to complications. And because I was fat, they probably wouldn’t save me. And when I got COVID in July 2021, it wrecked me, as I knew it would.

I now have long COVID (or post-COVID syndrome). This includes diagnoses of chronic fatigue, of post exertional malaise, and of brain fog which is a softer term for brain damage. My immune system, struggling before, seemed to

Break.

Malfunction

Crack.

In the months immediately following my first COVID infection, I developed chronic ear infections that lasted months, cystic acne for the first time in my life, antibiotic resistance, and infections due to the antibiotics.

I spent months laying on the couch, thinking, “I should work, I should work,” unable to move much less write. Even after I recovered, I was still sick. Any passing virus catches me. I wake up with fevers a few times a month. I still get recurring ear infections and will be getting ear tubes, like a toddler. I got shingles decades before my insurance would allow the vaccine.

And I am always, always in pain. Sometimes I don’t even notice. But as I write this, my wrists ache. My legs feel cold and sore. I have cuts and bruises on my legs, origins are unknown. It’s likely I have Ehlers Danlos syndrome. My foot is broken, I almost forgot. But it is certain, according to the Long COVID Clinic at UT, that I have long COVID. More than anything else, I am exhausted. After I teach a class, I need a nap. After I write, if I can focus enough to write, I need to sleep. If I work too long one day or do anything (go to a concert, a play, or Target), I will need the next full day to recover. Maybe I can read, write, or watch TV from bed.

But I teach 3 times a week, I have weekly doctor’s appointments, I try to keep my cat happy(ish), and I keep myself fed. How do I write? Read? And perhaps, most importantly, perform the role of a graduate student, a role I have been performing for years now? How do I perform my commitment to the difficulty of school, to the rigor, to the lack of sleep, and to life? It wasn’t healthy when I could do it. This performance is impossible now.

I mourn the performance of someone I never was and never wanted to be. I do not wish to be abled. I want the world, academia, work, and words to be accessible.

I can write and read. Slowly. In tiny bursts. With a thesaurus (which I need because of brain fog) and wrist braces. I often write in bed (like Frida Kahlo and Esme Wang, I believe) when I am in a good mood.

Travel is hard. This has changed my research plans, and methodologies. It has made conferences fewer and farther between (though more environmentally friendly). It has slowed me down tremendously, slowly trudging along to a finish line that seems just out of grasp. How will I publish more articles as I dissertate when I need to sleep for 2, 3, 4 hours every time I teach? How can I keep teaching with brain fog, when sometimes words feel out of grasp? How will I remain committed to my activist scholarship, to my students, and to my ethics? When will I need to apply for disability? (when, not if).

Rigour, for rigour’s sake?

And am I still a good student? Good students don’t sleep, not like I do. They don’t have to get accommodations to teach at home once a week. They attend department events. They travel to conferences, for research, and to institutes and trainings. They write, they read, and they do it until they finally, painfully, finish.

Graduate school is hard. But it shouldn’t be difficult for difficulty’s sake. And it should be accessible for those of us with disabilities, who, after all, have a whole different set of knowledges. Rigour, for rigour’s sake, is used to exclude and to isolate. To make competitors out of potential friends. Sometimes, it is used to weed people out.

So perhaps, in the future, with your own graduate students or when reflecting on academia in general, ask yourself, “Who does this rigour serve?” Is it for “the work” or is it because it is expected? Because it is supposed to be hard? Because it was hard for you?

I hope I will finish my PhD. I promise myself I will finish. I will wear the ridiculous robes and be hooded, performing through a different type of pain. If all goes according to plan, I will contribute to the sum of human knowledge—sick, disabled, and brilliant—while wearing heels with red soles.

Recommendations:

https://rebirthgarments.com/

and in particular Sky’s Manifesto

The work of https://samischalk.com/ (my academic hero)

The work of another academic hero Alison Kafer and LGBT Studies at UT

The work of Esmé Weijun Wang

Holly Genovese (they/them) is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at UT Austin but hails from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. They primarily write about art and anti-prison activism academically and you can find their writing in Teen Vogue, Jacobin, The Washington Post, The Chronicle of Higher Ed, and many other places.They are also a ghost tour guide, a sometimes teacher, an underwear influencer, an artist, a poet, and are also proudly neurodivergent and mentally ill. Reddit thinks their glasses are ugly, but Chrissy Teigan used to follow them on Twitter.

Follow them on insta and Twitter @hollyevanmarie and read more of their work at holly-genovese.com.

Thank you to the participants in the “Afterlives of Grief: Queerness, Disability, and Race” symposium at UT Austin for their feedback, in particular, Dr. Carlos U. Decena, Tal'y Wozner and my fellow panelists, in addition to the entire Grief, Queerness, and Disability Reading Group. I would also like to thank Dr. Sami Schalk and the “Feminist Visions in Times of Apocalypse: Collectively Evoking Joy, Love, & Healing 31st Annual Emerging Scholarship in Women’s and Gender Studies Graduate Student Conference” at The University of Texas at Austin.

In Moten, Fred, and Stefano Harney. "The University and the Undercommons: Seven Theses." Social Text 22, no. 2 (2004), 101-115. Moten and Harney write, “ it cannot be denied that the university is a place of refuge, and it cannot be accepted that the university is a place of enlightenment. In the face of these conditions one can only sneak into the university and steal what one can. To abuse its hospitality, to spite its mission, to join its refugee colony, its gypsy encampment, to be in but not of—this is the path of the subversive intellectual in the modern university. “ (101)

This is SUCH a good post! Thank you, Holly! I also developed chronic illness when I was in grad school and had a years-long process of getting a diagnosis (Lyme Disease and chronic Epstein Barr Virus) and it was just so incredibly sucky. I felt so alone in it, but then found amazing community outside of academia with other folks who were sick and disabled and that was a gamechanger for me. It also radicalized me in terms of seeing how gatekeeping academia is of folks who live with chronic illness/disability who can't or just don't want to participate in the normalized overwork. Thrilled to read this post, Holly. Can't wait to dive into your other writing!

This is such a needed post! Thank you for your words.